The Enemy

Links to the evidence referenced in this analysis appear in the sidebar to the left and within the analysis text. Simply click on a link (e.g. Figure iii) and a screen will pop up to display the visualization.

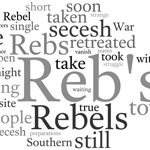

The Rebel army is viewed by Alcander in much the same light as Southern citizens. He does not seem to harbor any additional resentment toward them for their role as military enemy. In fact, Alcander curiously refrains from referring to the Confederate army as the "enemy." (See Figure 6.) Instead, as their civilian counterparts, they are called "Rebels" or "Secesh," but rarely "Southerners." (See Figure iv and Figure 5.)

Alcander is sincere in his beliefs that the war originated at the hands of the Southerners. His journal is filled with reflections on the war's progress, and he frequently bemoans the continued Southern resistance, as in this entry written on New Year's Eve 1863: "still this cruel war is waged with all the eagerness of madmen by the southerners[.] why O, why will they be so foolish. they must see by the steady progress we have made in this past year that we shall soon subdue them by force of Arms." The war is lamented for its cost, but is seen as necessary in order to end what the Rebels began. (See Figure i) Any harm these rebels came to, Alcander believed, was brought upon themselves. Following the Battle of Prairie Grove, Arkansas (a Union victory), he surveyed the ruined landscape. "go to the Secesh Hospitals[;] it is a very hard sight[.] all unkind feelings vanish as one looks upon those poor suffering men[.] it is true they brought it upon themselves[,] still it looks hard to see them suffer so." Alcander's comment that the Southerners "brought it upon themselves" is reminiscent of General William Tecumseh Sherman's infamous line: "You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will. War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it; and those who brought war into our country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out."

Alcander and the Union army in the West saw success in the Trans-Mississippi theater. While they experienced a few losses in small skirmishes and at the Battle of Chalk Bluff, Alcander was right to be confident in the campaigning prowess of the "western boys." With victories at the Battles of Pea Ridge and Prairie Grove, Arkansas, the enormous win at Vicksburg, Mississippi, and the successful sweeping of Confederate forces from Missouri and northern Arkansas, Alcander's encounters with the enemy typically ended with Union forces clearing Confederate troops from the field. The verbs commonly associated with the Rebels in his comments regarding military engagements are words like drove, cleared, escaped, leaving, vanish. (See Figure J.) The enemy is depicted as clearly inferior than Alcander and his army of "western boys." The day before victory was declared at Vicksburg, an armistice gave Alcander the opportunity to meet with the enemy. "meet the Rebs & have a chat[.] they look rough enough[.] still they will own nothing[,] but without doubt they must give up soon on account of food." The next day would bring the Confederate surrender of the city and a critical victory to the Northern war effort.

Another inferior breed of soldiers Alcander encountered in the South were irregular guerrilla fighters. Much of his war service was spent rooting out bushwhackers along the Missouri border and Mississippi River where they were wreaking havoc on Union supply lines. "nothing but a few guerrilla's [sic] in the vicinity" that "interrupt navigation on this River almost as they please at present & I guess will for some time to come." Guerrillas were not afforded respect as fellow combatants like Confederate soldiers were. Instead, they were dealt swift punishments for their acts of terrorism on the Union army. Alcander was witness to this treatment first hand while camped in Huntsville, Arkansas. "while here[,] Herron shot 9 bushwhackers[.] mostly leaders of bands."